Robert Broderson

Robert Broderson was born in West Haven, Ct. on July 6, 1920, and he died in Independence, Va. on March 12, 1992. He was a painter for forty-five years, from the time he entered Duke University as an older student after the war, to his last years in his studio in Independence overlooking the New River.

After he graduated from Duke in 1950, Broderson received a M.F.A. from State University of Iowa. Broderson then returned to Duke where he taught classes in drawing and painting for twelve years. He was an Associate Professor of Art when he left Duke after receiving a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1964. Broderson also taught at North Carolina State in Raleigh in 1967-68 and at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine during the summer of 1967. After the sixties, Broderson gave up teaching and devoted all his life to painting.

Highlights of Broderson’s career include the Guggenheim and Ford Foundation Grants, the inclusion of his work in shows at the Whitney, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Metropolitan, and his induction into the American Academy of Arts and Letters. In the sixties in New York, he was represented by the Catherine Viviano Gallery, which also represented the German Expressionist, Max Beckmann, and some of the American Abstract Expressionists.

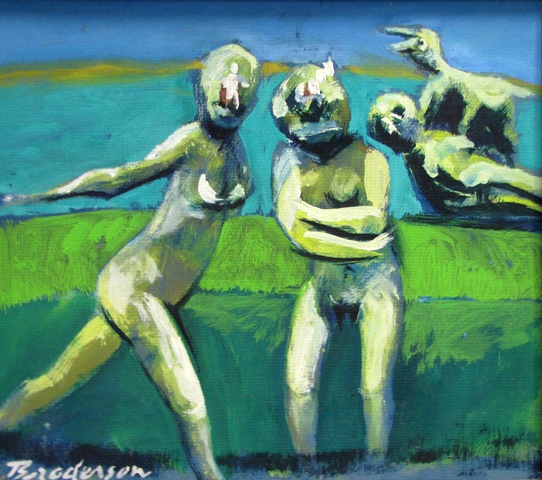

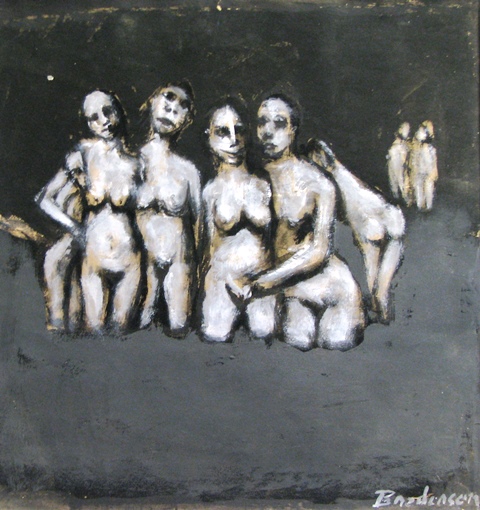

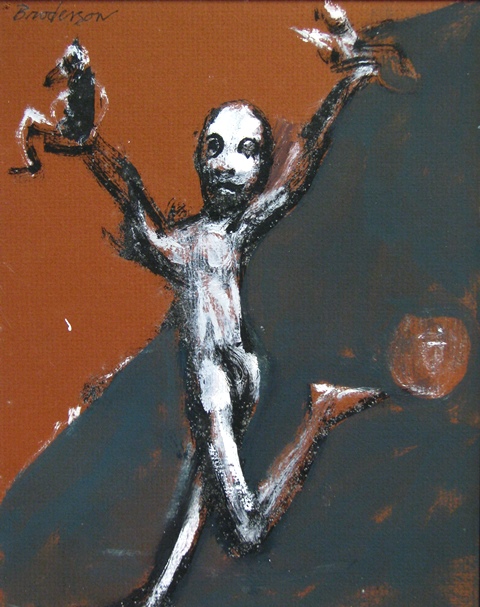

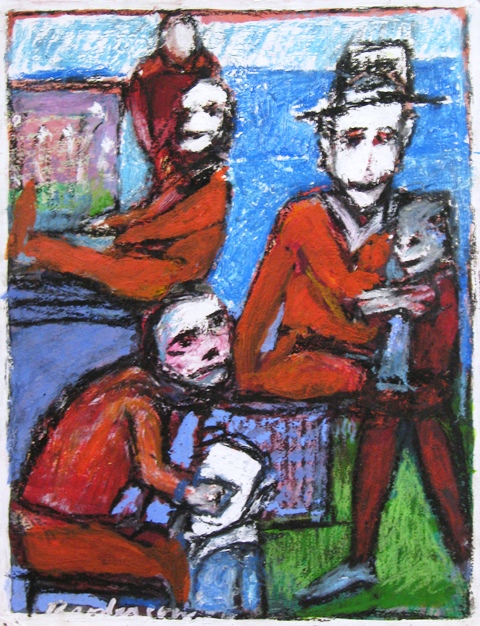

Broderson’s work began in black and white. The black was oil, India ink, pastel, or pen; the white was painted, left bare, or scratched off with a pen-knife. Broderson studied shades of black and white, brown, and gray for decades, off and on through experiments with color. In his later years, he moved into strikingly discordant colors of oil pastel. In between is a vast body of work, which testifies to the fertility of his creative imagination.

Broderson was a figurative painter, concerned with human and other figures. He sometimes invented new creatures in his work; often, a menagerie of people and animals seem to pose the perennial questions: where do we come from, where do we go. He studied all the varieties of human experience and expression. The people in his paintings, as he said, were not real people. He almost never knew what he would paint ahead of time. There are a few commemorations of public events in his painting, but they are rare. More often, his work developed expressionistically, in the process of painting. He worked on many canvases at once and never hesitated to rework what seemed finished. He hated dating his work, and he painted too many to worry much about titles. He often covered a whole wall with sheets randomly cut from a roll, and worked on each and all at once. He peopled whole worlds. He painted nearly every day for forty-five years.

currently there are no paintings available for sale by this artist

THE PAINTINGS BELOW HAVE BEEN SOLD OR ARE NOT AVAILABLE